APOCRYPHAL BARSOOMS I

Part 1 of a 16,700-word article

by Den Valdron

CONTENTS

Introduction

Barsoom

is Mars, and Mars is a Shared World

Other

Writers and Other Stories on the Shared World of Mars

A

Note About Space Travel

PERCY GREG

1880

ACROSS THE ZODIAC

The Story

Where on

Barsoom?

CAMILLE FLAMMARION

1884

REINCARNATION ON MARS

GRAFFIGNY

& LE FAURE 1889

AMAZING ADVENTURES OF A RUSSIAN

SCIENTIST

The Story

Is this Barsoom?

MacCOLL 1889

MR. STRANGER’S SEALED PACKET

Is this Barsoom?

ROBERT CROMIE

1890

A PLUNGE INTO SPACE

GUSTAVUS

W. POPE 1894

JOURNEY TO MARS, THE WONDERFUL

WORLD

On

John Carter’s World?

|

Introduction

In the Biblical terms, the Apocrypha

are the unofficial books that are not part of the formal bible, yet they

were contemporary religious documents of the Christian or Jewish faith.

As such, they’re not part of the "official" religious canon, but represent

a semi-legitimage body of external lore.

Burroughs Barsoom stories constitute

the nine novels and six novellas written by Edgar Rice Burroughs.

This is the ‘canon’ or the ‘true and official’ Barsoom.

In a larger sense, the canon includes the Moon Maid, which references

Barsoom, as well as Carson’s Venus, which also references John Carter,

though more indirectly. The Barsoom series makes use of the

Gridley Wave, which means that it connects to Pellucidar, and Pellucidar

connects to Tarzan. Thus, the larger canon is all of Burroughs

inter-relating series, all of which, including Caspak and Poloda, must

be deemed to be taking place within the same Burroughs universe.

Everything else, including fanfiction,

comic strips, comic books, pastiches, artwork, movie treatments,

etc. is ‘unofficial’ stuff, outside the formal canon. The stories

of George Alec Effinger, the strips of John Coleman Burroughs, the work

of Alan Moore and discussions of Dick Lupoff are all Apocryphal.

And by and large, it’s troublesome apocrypha that doesn’t fit well with

the canon.

John Coleman

Burroughs' Green Martians, for instance, are drawn to conform to the

requirements of a newspaper strip and look nothing like the written descriptions.

Comic book stories either tell the official stories but get them wrong,

or tell new stories, but make such changes in characters that they’re not

consistent with the original works. But then again, this is

why the Apocrypha are Apocrypha, because they don’t quite mesh with the

Canon.

But there’s also another vein of

Apocrypha I propose to mine here. And that is, the Mars stories

of other writers from Burroughs time period between 1880 and 1940.

There is a basic commonality to most of the Mars stories by different writers.

They were, after all, writing about the same world, and sharing the same

assumptions.

Barsoom

is Mars, and Mars is a Shared World

Mars was well established both in

science and the popular imagination. The moon was originally

the world on which fantasists had set their journeys to outer space.

As late as the 1830's, hoaxes and stories about life on the surface of

the moon were being published. After all, the moon was pretty

huge in the sky. But through the 17th and 18th century as telescopes

improved it was increasingly clear that the moon was a dead, waterless,

airless world devoid of life. The possibilities of imagination

were closed off for the moon.

For Mars, those possibilities were

opening up. Telescopes, from Galileo on, showed Mars as a globe.

Moreover, features were discernible. In the 18th century, astronomers

clocked the Martian day, discovered the polar caps and watched them swell

and shrink. Mars was a world with a day the same length as our own,

with seasons like our own, divided into discernible regions of light and

dark, ice and snow. Clouds and storms were observed, proving

that Mars had an atmosphere and weather. Reputable astronomers speculated

about the possibilities of life and habitation.

Meanwhile, around this time, theories

of evolution and cosmic formation were developing and mixing in popular

consciousness. A kind of cosmic theory of evolution,

of life progressing ever upwards was emerging. Darwin’s theory

of natural selection was morphed into a sort of inevitable progression,

from fish, to frogs, reptiles, dinosaurs, mammals and ultimately humans.

In popular imagination ‘man’ was the inevitable ultimate result of evolution,

at least up to this point.

Thus, the thinking was that the

beings of other worlds would themselves be human, or reasonably close with

slight variations. The notion that alien beings might be radically

unlike ourselves was, if not heretical, certainly not unquestioned, though

people like Percival Lowell and H.G. Wells and the more strictly rational

argued like this.

The notion that life went through

a cycle of birth to death. Life began, grew, evolved to its pinnacle

as humans and animals were born, grew, and reached their peak.

And then, humans and animals, over time, aged, grew weaker and eventually

passed away, as did Life in general and even planets. This

shifted into a kind of notion explaining the solar system.

Venus the young world full of wet rains and primeval beasts, likely hot

and lush, full of oceans and primitive jungles. Earth

was the ‘just right’ world, in its prime, with the proper balance of ocean

and land, of rains and sun, sporting the sophisticated pinnacle of life,

man itself. Mars was the older world, past its prime.

Its air, self evidently thinning, its mountains and continents wearing

away, its oceans drying up, the whole planet cooling off. It

seemed logical that if Mars was further along than Earth in the cosmic

life cycle, that it would have life and intelligence, and that these would

be further advanced than ours. But further advanced was not

necessarily superiority, Mars was in its decline, and thus the intelligences

of Mars were in decline.

Apparent proof of intelligence on

Mars, and of the decline in that world, came in 1877 when Schiaparelli

announced his discoveries of Canals. Canals were big

during this time, the Suez canal bisected Africa and Asia, uniting the

Mediteranean with the Red Sea. The Eerie and St. Laurence canals

of North America extended shipping for hundreds of miles. The

Panama and Nicaragua canal projects promised to separate North America

from South and unite the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Schiaparelli’s

‘canali’ included 66 razor straight lines, some of them parallel, some

of them crossing each other, running from presumably wet dark areas, through

dry regions. While people might argue over whether they were natural

or not, it was hard not to see them as the work of intelligent beings engaged

in irrigation on a dying, drying world.

It was also the same year that Mars'

two moons were discovered, moons unlike any others in the solar system.

It was a year of conjunction, of close approach, which happened only once

or twice every few decades, so most telescopes were engaged with Mars.

Mars was very big and very big news in popular consciousness.

For scientists and for writers and

the public, Mars was hardly a blank place. It was a very well defined

world, no more or less mysterious than Africa or Asia. We knew

what it looked like from a distance, we knew its size, its day, its weather

and seasons. We knew the light areas were likely deserts, we

knew it was an old world so that erosion had worn away its mountains and

continents. We knew that its seas were diminished remnants (as Schiaparelli

believed), though that perception evolved to the belief that its seas were

entirely gone (as Lowell believed), but still, moisture survived in the

sea bottoms. We knew it had life, probably much like our own.

And from the evidence of Canals, people assumed that there were intelligences,

a civilization probably much like our own, but trapped upon a dying world,

undertaking great works.

|

The result is that it was

quite natural for writers writing about Mars to essentially be writing

about a very similar place. As I’ve said, it's not a

blank slate, but rather a well known territory and writers wrote within

the knowledge of that territory and the science and pseudoscience beliefs

of the time. Mars, from the very beginning was a shared world,

much the same way that the American west was a shared world for different

writers fictional and non-fictional characters. Writers who

wrote the west took a shared setting, they weren’t dropping samurai and

gorillas in, but working with cowboys and gunslingers. Mars,

in its own way, was almost as rigourously defined for writers. So,

they tended to use the same ideas, and the same tropes over and over.

And it wasn’t just a dry dying world of deserts crossed by canals, with

evaporating seas and sheltered valleys.

The faculty of telepathy, for instance,

is almost universal. Telepathy was considered an advanced mental

faculty, a higher faculty, so it was only natural that the Martians, being

from an older world, should possess it in some degree. Besides which,

it got us neatly and quickly around the language barrier.

A great many, perhaps most of the

Martians encountered, including Burroughs, were human. Their skin

colours might vary, but they were basically human beings, though usually

from a culture more technologically or intellectually sophisticated.

Because Mars was believed to be a dying desert world, there was a subtle

tendency to draw upon elements of Arabian culture or 1001 nights by many

writers. The Arabian culture, or bastardized visions of it

in Europe, were seen as an old civilization, past its prime and in decline.

So often bits of that would get mixed up in various ways.

Alternately, writers might choose

to emphasize the ‘evolution’ of Martian society, of a race whose intellectual

attainments choked off its moral or its emotional side. There

were a number of stories depicting Martians whose intellectual sophistication

was balanced by a lack of emotion and often a lack of will or motivation.

These Martians were apathetics, accepting the fate of their world, lacking

the will to struggle. Of course, others were depicted as being

made monstrous for logic without emotion. H.G. Wells invaders

were the ultimate expression of this.

Apart from humans, interestingly

enough, winged manlike creatures were the next most popular. Partly,

of course, this was the apple not falling far from the tree.

Angels lived beyond the earth in Heaven. So it’s not rocket

science to imagine angel-like winged beings living beyond the earth on

worlds in outer space, like Mars or Venus. And it did make

a certain kind of sense, after all, the gravity was lighter so flying creatures

were more plausible. Between 1890 and 1920 there were at least eight

stories or novels featuring this sort of Martian, including the creatures

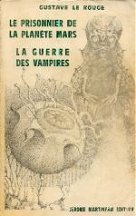

of H.G. Wells’ “The Crystal Egg” and Gustave LeRouge’s “Prisoner of Planet

Mars.”

Other mythical or semi-mythical

creatures, often variations of human forms were seen. There were

four Martian stories between 1890 and 1920 which featured dwarves of various

sorts, often cave-dwellers. Giants showed up a few times, though

usually these were human giants. Even H.G. Wells’ creatures

began to show up repeatedly.

Mars was considered to be an Earthlike

world, so writers filled it with earthlike plants, mosses, trees, grasses,

shrubs, and usually mixed the colours up, adding red and purple after the

planet’s colour. Earth was a green and blue world, Mars was

obviously a world of reds and rust. And of course, it was presumed

to have its own animal life, both similar and different from Earthly fauna.

Again, sometimes the apple didn’t fall far from the tree, both Wells and

Arnold included apes on their Mars.

So, Gustavus Pope’s Journey to

Mars, Edwin Arnold’s Gulliver Jones and Gustav LeRouge’s Prisoner

of Mars weren’t the sources of Burroughs' A Princess of Mars.

Rather, they were all shaped by the same planet, including the views of

the planet, the beliefs in ‘inevitable evolution’ and life cycles on planetary

scales. In a similar way, the Cisco Kid wasn’t the inspiration

for other fictional or real gunslingers, they were all products of the

same setting.

It’s all happening on the same Mars.

It may be an imaginary Mars, and each writer may go off in a different

direction, but in a sense, the Mars of novels and stories of 1880 to 1940

was a shared universe, a shared world.

Burroughs just called his Barsoom,

but the reality is, that he was simply writing in the same metafictional

Mars that everyone else was. But here’s the thing about Barsoom.

There was just so damned much of it. Burroughs Barsoom stretched

out to nine novels and six novellas, thousands of pages and hundreds of

thousands of worlds, and within that, swamps, rivers, mountain ranges,

dried sea beds, cities, races, religions, cultures and history. In

short, Barsoom overwhelms all the other renditions of the fictional Mars

of this day. In contrast, Matthew Arnold wrote only one Mars

novel. Otis Adelbert Kline wrote two and a novella. H.G.

Wells wrote a novel and short story, but only the short story depicted

the actual planet. Gustave LeRouge wrote two novels, but only

one was actually set on Mars. Pretty much everyone else wrote

single novels, short stories or included Mars visits as parts of larger

works. Many of the other works, because of their smaller volume

also tended to describe smaller slices of Mars. Arnold’s Gulliver

Jones wanders about in a relatively small area, Wells’ story describes

only a single valley. So the result is that on any composite

vision of Mars, Barsoom tends to occupy a lot of the territory.

So why not just call it all Barsoom, since Mars is no longer the world

we dreamed of.

Other

Writers and Other Stories on the Shared World of Mars

That old shared Mars, the one that

endured from 1877 to 1950, the one of science and myth, popular consciousness

and writers fantasy, has vanished now. The Mars revealed by

space probes has largely replaced it. So Barsoom is,

for better or worse, a good a name as any for that older shared Mars.

Now the thing is, if you’ve got a shared meta-world, then the natural temptation

is to locate it all together. Thus famous real and fictional gunslingers

crossed paths in the old west, and H. Rider Haggard’s Africa rubbed shoulders

with Burroughs.

More recently, there have been literary

pastiches by people like A. Bertram Chandler, George Alec Effinger and

Alan Moore placing John Carter in conflict with Wells' Martian invaders,

throwing Gulliver Jones or Otis Albert Kline’s Mars into the mix.

In part because of the connections to Burroughs between Wells, Arnold and

Kline, I’ve explored and tried to place each of these writers' "Mars" on

the same world as Barsoom.

But anyway, if these three writers'

works can be incorporated into Burroughs Barsoom, what about others?

Are there other writers stories or novels about Mars that will fit in too.

Actually, there are. Now mostly obscure and forgotten, there

are a number of stories and novels from between 1880, after the discovery

of the canals and moons of Mars, and 1940 when the vision of Mars as a

live world had faded.

Most of these works are out of print

and quite hard to find. This poses some problems and if you

want to track them down and read them you may well be out of luck.

Moreover, because I myself haven’t read most of them, I can only go by

brief descriptions. Descriptions which are extremely tantalizing,

but which, unfortunately do not allow the sort of detailed and thorough

analysis of geography, biology or culture, which would allow us to place

a work in context on either Barsoom or the geography and geology of real

Mars. Unfortunately, I’ve only got the broadest strokes to work with,

and thus, my comments are wholly speculative and I can hardly place too

much weight on the poor delicate things.

Finally, I must note that in some,

perhaps in many cases, some of stories will not and cannot fit on Barsoom

at all, or contain elements that are completely inconsistent with what

we know of Barsoom. For instance, the Human Pets of Mars features

Martians who are essentially ten-legged octopi, or decapods, who have no

resemblance to anything, and who breeze back and forth easily seem completely

incompatible with Barsoom. There’s also Thomas Edison’s Invasion

of Mars and Nikola Tesla’s Invasion of Mars about either of

which, the less said the better, but feature fleets of Earth spaceships

travelling out to wreak devastation on the red planet. Inspired originally

by H.G. Wells, these were simple potboiler newspaper serials, bereft of

imagination or intelligence, but which presumed technology and actions

that simply cannot have taken place in Burroughs universe.

And of course, this work ignores

the Burroughs inspired Mars stories of the 50's and 60's, like Michael

Moorcock’s "Michael Kane," Leigh Bracket’s Sword of Rhiannon

and "Eric John Stark," and A. Bertram Chandler’s Alternate Mars.

This obviously cannot be complete.

There are doubtless novels and stories that would fit that I’ve missed,

as well as many that won’t fit. But that’s okay.

Mostly, it just has to be interesting and entertaining.

A

Note About Space Travel

Initially, I was going to dismiss

any mention of Earth or Martian spaceships as being completely contradictory

to the Burroughs universe. Where Earthlings or Martians travel

back and forth by spaceship seemed at first to be quite contradictory to

the established Burroughs canon.

After all, in the Moon Maid, Burroughs

establishes that the first official Barsoomian space expedition to Earth

is launched in the 21st century, in 2015, and is lost. This

is followed, a few years later by Earth’s first expeditionary ship to Barsoom

in 2024, which makes it only as far as the moon.

So talk of rocketships or spaceships

in the late 19th or early 20th century seems ludicrous in the Burroughs

universe. Didn’t, oughtn’t, can’t and ain’t happening.

If they can’t manage it well into the 21st century, there’s no chance in

the late 19th.

However, I’ve reconsidered.

Carson ‘Wrong Way’ Napier builds himself a rocket and flies to Mars in

1932, nearly a full century prior to the ‘Moon Maid’ expedition.

Now to be fair, he doesn’t get to Mars, but he does wind up on Venus, so

there’s proof that local interplanetary distances can be traversed by Earthlings

in the earlier part of the 20th century, and perhaps even slightly earlier.

And further, given that we’ve borrowed

War of the World and "The Crystal Egg" from Mr. Wells, we must assume

that technology from the Martian invasion was in fact cannibalized and

might have made it into the hands of intrepid space explorers or inventors.

We might also consider that in his writings, anti-gravity is a fact of

at least one of his novels, First Men in the Moon, where his protagonists

encounter insectlike beings who occupy the outer (but not inner) surface

of the Moon. Anti-gravity shows up in quite a few space voyages.

The question of course, is why there’s

such a huge gap between Carson’s lone expedition of 1932 and the Moon

Maid expedition of 2024? This problem, on its first look,

seems insoluble. But I think a couple of factors come into play.

First, it is likely that the Martian

invasion of the War of the Worlds put a damper on any thoughts of

official space travel. Earth had survived an invasion, there

was no future invasion apparently forthcoming, why go looking for trouble?

Space travel was not an official priority, and was unofficially discouraged.

This left only the occasional wealthy malcontent or consortium of intrepid

and financially secure explorers to take a chance.

Secondly, we must note that the

Barsoom was not only an official, but a major expedition. It had

a large crew, provisions for years, staterooms, etc. The Moon

Maid's Barsoom was the equivalent of a Battleship or of Admiral Perry’s

Great White Fleet. Meanwhile, Carson’s attempt was in comparison,

the equivalent of a relatively small sailboat crossing the Atlantic or

Pacific. Yes, it’s theoretically possible to cross the Atlantic

in a sailboat, but there’s a very good chance of not making it at all.

Those space travellers of Earth

of the late 19th or early 20th century were probably sailing against the

odds, and for those few who managed to reach a neighboring world and live

to tell about it, there were likely many who set off and were never heard

from again.

Out in space, even in the mid-19th

century, Barsoom’s civilization definitely possesses anti-gravity technology,

through its mastery of the eighth and ninth rays, and during the reign

of the Warlord, in Swords of Mars, begins to make exploratory flights to

Thuria. Yet, the trips to Thuria are not so much new or revolutionary

technology, as the application of technologies (environment seal, life

support, anti-gravity etc.) that Barsoom has had lying around for thousands

of years.

Further, with respect to Barsoom,

we note that technology is not uniform but varies locally.

Helium’s flyers are the most advanced known. The First Born’s

flyers, however, are designed for submersible flight. Jahar’s

flyers are technologically inferior compared to Barsoom. Kaol

has no flyers at all, though they later acquire them. Meanwhile,

isolated regions such as Manator, Ghasta and Bantoom have no flyers and

no firearms. Even more isolated societies, such as the Orovars

of Horz, have even lower technology.

Yet, we must note that once upon

a time, the level of technology on Barsoom was higher even than that of

Helium today. Indeed, in another paper, I’ve speculated that

Thuria may actually be an artificial world, created tens or hundreds of

thousands of years ago by the fallen civilization of the Orovars.

So it’s possible that somewhere on Barsoom, some lost and isolationist

city still possesses the capacity to travel through interplanetary space,

should it wish to.

So, theoretically, we might have

isolated spaceships from Barsoom, the products of isolated and isolationist

cities, which manage to make it to Earth. So, in the context

of Burroughs universe and Barsoom, we might be prepared to accept some

limited occasional normal space travel between worlds.

PERCY GREG

1880

ACROSS THE ZODIAC

In 1880, one of the first Mars

novels was Percy Greg’s Across

the Zodiac: Story of a Wrecked Record. Allegedly, this chronicled

and event taking place 50 years before, which would place it in 1830.

The

Story

In this account the Astronaut,

a privately-built ship of 150 feet long, 50 feet wide and 20 feet high,

was the first human spacecraft to travel to Mars. The

Astronaut was propelled by Apergy, but a force that had to be generated

and controlled, something more similar, perhaps to the Barsoomian bouancy

rays. The electrical generators recycled the ship’s air and powered

the Apergy machines which directed atomic force to repel the Sun's

gravity. Which seems like a very, very anomalous technology

for 1830's Earth.

Mars, the ship's destination, had

an "advanced race" practicing polygamy and atheism; the Martians also had

dirigibles, poison-gas guns, electric tractors, 3-D talkies, and the duodecimal

system. His Martians had developed a form of utopia based on advanced

technology and telepathic ability, which enabled them to punish people

for wrong thoughts. However, they did not have resistance to a disease

of earthly origin "contracted from rose-seeds," so the hero left in a hurry.

Actually, the Greg Martians don’t

seem all that much like Barsoomians. They aren’t fun loving

enough. The telepathy thing, of course, is shared with Burroughs,

Arnold and Wells, but they didn’t get that from Greg, or from each other.

Rather, all four authors, and many others, picked up on a pseudo-science

notion that was floating around.

Greg’s Martians are an ancient civilization,

so ancient, and so intellectually evolved, that they have lost touch with

feelings. They are passive and apathetic, with little interest

in the world around them.

This sort of "listless ancient decadence"

shows up again and again in Mars novels of the era. Before

Wells put his spin on things, the ultimate result of intellectual development

at the expense of emotions was apathy. The super-intelligent

civilizations of the Martians were frequently depicted as passionless,

placid and lifeless. The super-civilizations of these Martians

had no gumption, no motivation. In the end, they had not the

motivation to fly their own spaceships.

Wells of course put a different

spin on it. His super-intelligences were highly motivated,

the loss of emotions simply made them more ruthless and relentless.

Burroughs, for his part, restored vitality to his Martians, depicting them

as struggling valiantly if fatalistically as their world died slowly.

In a sense, in Burroughs, Barsoom is dying more quickly than its inhabitants,

so they’re kicking up a fuss.

Where

on Barsoom?

Does this mean that the passive

Martians are incompatible with Barsoom? Perhaps not.

Barsoomian civilization, the dominant cultures that John Carter knows,

are shaped by the great collapse. Everything from semi-feudal

slavery, city-state political organizations, the rule of war-chiefs in

the form of Jeds and Jeddaks , the emphasis on war and warriors over science

or trade, were all formed in the great collapse of the previous Barsoomian

civilizations. And the thing is, that although Barsoom is no

longer in a state of active collapse, these societies have not changed.

They are still shaped by that disaster.

But was this the only response to

the great disaster? Perhaps some societies, partially sheltered

from the ongoing collapse, simply turned inwards. They made

fatalism a religion, becoming intellectual, unemotional, passive, taking

very little part in the affairs of the planet. For convenience,

we’ll call them Apathetics.

On Barsoom, cities of Apathetics,

some of them conceivably preserving extraordinary levels of technology,

may exist in remote locations, uninvolved with the lands around them and

isolated from the mainstream of Barsoom’s warrior cultures.

So, conceivably, these Martians

might well tuck away neatly in some corner of Barsoom.

CAMILLE

FLAMMARION

1884

REINCARNATION ON MARS

1884 - Camille Flammarion - Les

Terres du Ciel (The Worlds in the Sky) (Marpon-Flammarion).

A man and woman who died at the top

of a mountain find themselves reincarnated on Mars, a touching reunion

that includes a few descriptions of martian flora and fauna.

Then a few years later, we have in 1889, Camille Flammarion writing -Uranie

(Marpon-Flammarion)

wherein a man awakens on Mars and meets his reincarnation.

I’m not sure if this fits into Barsoom

or not. Forget about any geographical description, and I have

no idea whether the flora and fauna is at all compatible. However,

Camille Flammarion is worth a couple of Burroughs footnotes (see

ERB's Personal Library).

First, because as an astronomer, he was noted for compiling all of the

observations of Mars over two centuries, a landmark and pivotal work of

scholarship which both Schiaparelli and Lowell built upon (See

the Valdron Barsoomian Geography Series).

Second, and for some purposes, much

more interestingly, Flammarion in his fiction popularized a notion that

people were reincarnated, not on Earth or Heaven, but on Mars.

This was apparently a fad. The significance of this shouldn’t

be underestimated, as arguably, John Carter, Ulysses Paxton and Tangor

appear to die, or are brought near death, before going off to their respective

worlds. I’ve called the phenomenon Astral Teleportation, but

quite possibly, it is actually death on this world and reincarnation on

another world. Burroughs once, talking about religion, expressed

a hope of being reincarnated on some other world, so perhaps he took this

critical idea directly or indirectly from Flammarion.

GRAFFIGNY

& LE FAURE

1889

AMAZING ADVENTURES OF A RUSSIAN

SCIENTIST

1889 Henry de Graffigny

& Georges Le Faure - Les Aventures Extraordinaires d'un Savant Russe

[The Amazing Adventures of a Russian Scientist] - Volume 2: "Le Soleil

et les Petites Planetes" [The Sun and the Small Planets] (Edinger).

The

Story

A team of French and Russian

scientists explore the Solar System on the Ossipoff.

Through three volumes, they explore the inner planets, the moon, and then

the outer solar system. In the second volume, they make a short

trip to Mars, where they meet the inhabitants.

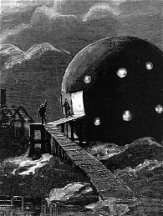

The heroes arrive on Phobos, which

is atmospherically connected to Mars, and travel in a balloon down to the

Red Planet, wearing pressure suits. During the next five chapters, they

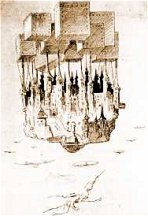

meet winged humanoids, masters of an aerial technological civilization.

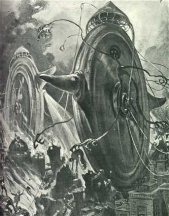

Artists drawings depict bald, insect-winged human-like creatures wearing

robes, as well as a remarkable floating city in the sky, hung from box

kites.

Is

this Barsoom?

All right, in John Carter’s Barsoom, Thuria is not normally

atmospherically connected to Mars, no iffs ands or butts. On

the other hand, in Beyond the Farthest Star, Burroughs' Poloda

solar system features a ring of worlds all sharing an atmosphere, so that

one can literally fly an airplane from one world to the next.

Well, if this is the normal state for Poloda, then obviously,

this is one more peculiarity of physics in Burroughs universe.

Mars and Thuria are extremely close bodies, among the closest in the solar

system, so its possible that this same kind of phenomena may appear between

Barsoom and Thuria under freakish special conditions. Our explorers

may well have been mistaken when they took it for a permanent state.

As for the winged humanoids, these are not part of Burroughs

writings, but they do seem similar to the flying Martians of Wells’ ‘The

Crystal Egg’, as well as to the butterfly winged ‘little people’ of Otis

Adelbert Kline’s Swordsman of Mars as well as a handful of other

similar creatures as you will see in the subsequent reports.

MacCOLL

1889

MR. STRANGER’S SEALED PACKET

In Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet, MacColl was also

something of a pioneer in his choice of subject. It was the third novel

in English about Mars to be published. In 1880 Percy Gregg published Across

the Zodiac, and in 1887 Hudor Genone published yet another novel with

Mars as its subject,

Bellona's Bridegroom: A Romance. MacColl's

Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet then followed in 1889, and before the

turn of the century, another eleven novels about Mars were published in

English.

McColl flies off in an armed and armoured spaceship to

visit Mars. Once he gets there he discovers that Mars is quite

habitable. It possesses gigantic prehistoric seeming animals,

and vegetation similar to Earth except that it tends to be scarlet or purple.

McColl’s stranger describes spectacular scenery, including

an Ocean:

“It was a glorious spectacle.

A majestic ocean lay before me, rolling its heavy swell against the rocky

bases of a long, sweeping range of precipitous mountains underneath me.

This range was broken and indented in many places by deep ravines, down

which foaming torrents rushed headlong, forming numberless cascades and

waterfalls, the confused noise of which was almost deafening. The sea ran

in among the clefts and fissures of the rocky shore in long and narrow

streaks--in some places cutting whole portions off and forming them into

islands.”

The Martians turn out to be human, a race or nation of people

calling themselves the Gremsun. Their skin colour is bluish

and they have large hazel eyes. Both features are caused by the food

they eat. The Martians, including men women and children dress

uniformly in what looks essentially like a Victorian bathing suit--a single

garment, exposing only the head and neck, the arms below elbow, and

the feet and legs to about the knee, red for men and green for women.

Both sexes had short, black, curly hair. They all speak and act like

Victorians, they’re civilized to a fault. These people are

dull, dull, dull. Their technology is sophisticated, they distill

their food from the air. Though the society is technologically advanced

in that it has self-propelling carriages, electric light and phonographic

machines that can register speech as writing, it lacks totally the technology

of war.

This is unfortunate for the Gremsun because Mars also

has barbarians, who are called the Dergdunin. The war with the barbarians

gives Stranger the opportunity to play the hero, as the spaceship is also

equipped for defence and attack, and so he saves the peaceful civilized

Gremsun from the barbarian hordes.

The Stranger also winds up falling in love with and marrying

the daughter, Ree, of the Martian family he has been staying with.

The Stranger eventually brings his Martian wife back to Earth for sightseeing,

but it turns out, in a plot development that anticipates Wells, that she

has no resistance to earthly bacteria and dies. This by the way,

is not a particularly shocking development, Englishmen in the colonial

days were always travelling to foreign colonies and dying of local bacteria.

It was one of the known hazards of colonialism. The Stranger,

touched by tragedy, drops off his story with earthlings, and returns to

Mars to spend his life.

Is

this Barsoom?

If this is Barsoom, then we can only say that Mr. Stranger

has landed upon the dullest and most repressed and inbred part of the planet.

We can only place this as a Barsoomian society in an extremely isolated

and apathetic enclave.

That having said, many of the elements of Burroughs Barsoom

are present. The civilized nation with its super science, the

barbarians prepared to tear the whole thing down, the romance with a Martian

debutante.

Further, the blue skin of these Martians is remiscent

of Gustavus Pope’s blue-skinned Martians of Journey to Mars.

The biggest obstacle, apart from the Gremsun being so

weeny and pathetic, and the tedious pace of the novel is the fact that

the Stranger records a Martian ocean. Not on Barsoom buddy!

Still, it may be that the Stranger has been mistaken in his observations,

he may have surveyed one of the surviving seas, like Korus or the Opal

Sea. Or he may have observed a rush of water following the polar

melt.

Without the actual text, it’s hard to say.

Still, given other similarities, we might, for the time being, provisionally

locate this on Barsoom, although it’s not clear where exactly.

ROBERT

CROMIE

1890

A PLUNGE INTO SPACE

1890. Robert Cromie's A

Plunge into Space (prefaced by Jules Verne)

The

Story

This tale also featured a spaceship, the Steel Globe, a jet black metal

sphere, 50 feet in diameter, powered an electrically-generated form of

anti-gravity. It was secretly built on an undisclosed site in Alaska, and

its destination was, once again, Mars.

This tale also featured a spaceship, the Steel Globe, a jet black metal

sphere, 50 feet in diameter, powered an electrically-generated form of

anti-gravity. It was secretly built on an undisclosed site in Alaska, and

its destination was, once again, Mars.

The more highly developed Martian reason had made Mars

a paradise even though growing conditions had gotten worse. But their reason

had also been developed at the expense of their emotions. They had lost

their vitality and motivation too. In this novel, that meant the Martians

could not get enthusiastic about anything. Not only could they not get

enthusiastic about arrivals from Earth; they could not get enthusiastic

about their own space travel. They had it and lost interest in it.

In short, they were our second great example of that stream

of Barsoomian culture we choose to call the Apathetics.

GUSTAVUS

W. POPE

1894

JOURNEY TO MARS, THE WONDERFUL

WORLD,

ITS BEAUTY AND SPLENDOR,

ITS MIGHTY RACES AND KINGDOMS,

ITS FINAL DOOM.

Pope was an American doctor living in Washington D.C.,

who wrote both fiction and nonfiction. He followed up his Journey to Mars

with Journey to Venus, introducing some of the same characters. He also

did an inner world novel, and a fairly well received book about Shakespeare.

Arnold's Gulliver Jones was never published in the United

States during Burroughs' time. It only appeared in England. Pope has a

leg up in that his books were published in the US. But of course, we've

no evidence that Burroughs ever saw either.

Still, Pope's book has his adherents who argue that its

possible claim to have inspired A Princess of Mars is as good or

better than Gulliver Jones. Among the proponents was noted SF critic

and historian Sam Moskowitz. The novel begins with our protagonist

Frederick Hamilton, a Lieutenant in the US Navy, serving on the USS Albatross

in the Antarctic seas when it wrecks. Hamilton and a Maori seaman (a comic

relief racist stereotype, unfortunately) are cast up on a barren rocky

island, although at the ends of his strength, he manages to rescue a weird

looking stranger and then passes out.

When he wakes up three weeks later, he's on his way to

Mars. Hamilton has encountered an expedition of red, yellow and blue Martians,

who use telepathy to communicate with him, and who travel space by riding

the magnetic lines between the two planets' poles. The blue-skinned Martians

are the "Nilata," and the yellow-skinned men are the "Arunga," though this

may refer to their cities or nations, rather than their races.

Obviously, these three races are fairly suggestive, since

Burroughs Barsoom also has its red and yellow Martians. Coincidentally,

Burroughs yellow Martians are inhabitants of the north pole, and are shown

to have mastered magnetic technology, areas that figures prominently in

Pope's story.

Travel between Earth and Mars in Gustave's story, involves

travelling along magnetic pathways, a sort of cosmic short cut, which begins

and ends at the north pole of each planet. This is why Hamilton meets his

Martians at their base at Earth's south pole, and why he winds up in the

sea around the pole.

As for Blue Martians, well, Burroughs does not record

any. But Burroughs does have blue haired Thurians, who I've argued in Secret

of Thuria are actually an isolated Barsoomian colony from their

previous civilization. So it might well be that this expedition includes

Okars, Red Men and Thurians. Alternatively, at least one of the other

Martian novels, McColl’s Mr. Stranger’s Sealed Packet provides for

a race of 'blue' Martians, so this may simply be a race undiscovered

by John Carter. I wonder if they sing?

Interestingly, Hamilton at first does not realize these

people are Martians. Why would he? His first theory is that they are inhabitants

of Pellucidar, or at least, of a hollow inner earth, and have come into

the surface through the polar opening. It's a weird little overlap with

Burroughs, notable because, as I said, I believe Hamilton also wrote

an inner world novel, which further identifies us with Burroughs universe.

Anyway, on arriving at Mars, the spaceship, riding lines

of magnetism, splashes down near one of the poles, winding up in a shallow

polar sea. This is, itself, not necessarily inconsistent with Barsoom.

The Martian poles are the final great bodies of water on Mars and feed

the canals, so it stands to reason that in the summer, their edges might

be slushy and produce a rim of lakes or seas.

Hamilton finds that the Martians, like John Carter's Barsoom,

combine a feudal society and swordsmanship with high technology. They have

crystal globes (shades of Wells and Arnold), 'ethervolt cars' which use

anti-gravity batteries, and spindle-shaped aircraft, both of which are

fairly reminiscent of Barsoom's flyers.

I'm not too concerned with differences in names and terminology,

after all, both Hamilton and Carter are translating their respective Martians

into English, so its quite possible that they might take the same terms

in the same language and render it differently in English.

Hamilton discovers, like Carter, that his strength on

Mars has doubled, though he attributes this to more oxygen in the air,

rather than gravity. He observes that the Martians travel on giant birds,

much like the Malagors that appear in two of Burroughs Martian adventures,

or the Gawrs that appear in Kline’s two Martian adventures.

Anyway, once he arrives on Mars, Hamilton travels about

a bit, visiting Mars wild seas and encountering sea monsters within, traveling

through kingdoms, enjoying banquets and festivals. He learns many interesting

things about Mars, including that the population is eight billion, that

the canals visible from space are actually densely packed urban areas,

and other cool things which are apparently quite incompatible with Barsoom.

During one festival, he rescues the beautiful yellow-skinned

Princess Suhlamia from drowning, and of course they fall in love. This

introduces the worm of intrigue, since Prince Diavojahr also had his eye

on Suhlamia. Diavojahr is a bad egg, since he's half Plutonian. He challenges

Hamilton to a duel and is soundly beaten. Diavojahr then conspires to have

Hamilton accused of treason and condemned to death in order to blackmail

Suhlamia into marrying him. Luckily, some of Suhlamia's friends rescue

him.

But there's a bigger problem. Phobos and Deimos, Mars

Moons, are about to fall on it. Or perhaps the danger is a rain of asteroids

or meteors. This isn't really clear from my internet searches. But the

imminent threat is the reason for the original expedition to Earth. The

Martians are looking to relocate. So off Hamilton goes to Earth to look

for a tidy place to pack eight billion Martians.

While he's gone, disaster strikes, but not in the form

of asteroids. Rather, Prince Diavojahr has instigated a palace revolution

and is trying to take over Princess Suhlamia's nation. He threatens to

shut down the magnetic transmitting station to make it impossible to return

to Mars. The novel ends with Hamilton passing on the manuscript he has

written, preparing to return to Mars.

But things must have worked out all right because when

next we see Hamilton in Journey to Venus he's with his Princess Suhlavia,

time has passed and they're heading off to Venus. I can only assume that

the Phobos and Deimos, or the asteroids and meteors missed Mars after all.

Anyway, that's as much as I've been able to glean from

internet researches. The book is described as slower paced than Burroughs'

book. Critics have noted that it's often dragged down by expository travelogue

stuff, or Jules Verne technobabble. Hamilton, as a protagonist, is too

perfect and therefore dull. And of course, the racist treatment of the

Hamilton's Maori companion is offensive.

Alas, there's only one Burroughs, and if his predecessors

had had his touch, we would have remembered them better.

On

John Carter’s World?

Sounds familiar? Published some 18 years before

A Princess of Mars and 11 years before Gulliver Jones, science

fiction historian Sam Moskovitz has written a paper suggesting that it

may well have been the real inspiration for Burroughs' work.

The similarities lead to the novel being re-published in the '60s, with

a foreword by Moskovitz, setting out his theory. Apart from

the many similarities, this novel was actually published in America.

Gulliver Jones was published only in England.

Is Frederick Hamilton's Mars really John Carter's Barsoom?

Setting aside the hard kernel of apparently contradictory material which

I'll address later, there are endless remarkable similarities. The red

and yellow races, the polar/magnetic thing, the high culture/feudal society,

the princess, the derring do, the giant birds, swordplay and anti-gravity

ships.

The one really difficult thing to swallow is that these

Martians have space travel, or at least, some limited and special type

of space travel involving riding magnetic lines. This seems beyond the

technology we know of in Helium. But then again, Helium may not be the

technological apex. It may be that some isolated and isolationist city

has preserved some of the space travel technology of the previous age.

In any event, its clear that the space travel of the Martians depicted

here is not conventional space travel, but a sort of special loophole,

which may not be very easy and in fact which may only exist under certain

conditions.

In fact, if we wanted to play it this way, we could suggest

that this isolationist city of either Blue, Red or Yellow Martians may

be the willing or unwilling, direct or indirect source of the anti-gravity,

space travel technology used by Earthlings in the late 18th and early 20th

centuries.

Unfortunately, with the information that we have, we can't

really locate Hamilton's journeys on Mars or Barsoom with any reasonable

certainty. It's likely, given the yellow Martians, that he's mixed up with

the North Pole. He clearly is landing in one of the polar regions during

the height of the summer melt in that hemisphere, and he does seem to go

on a bit of a tour through the populated regions. But unlike Wells, Arnold

or even Le Rouge we don't have enough geographical information to work

with.

So, what about the apparent contradictions? The seas Hamilton

describes, the eight billion Martians he reports, Diavojahr's half-plutonian

ancestry, the heavily populated canal regions and so forth? If these things,

any of them, are absolutely literally true, then there's no way that Hamilton's

world could be Barsoom.

Now, I suspect if I keep slagging the Wold Newton types,

I'm going to get into a fight sooner or later. But what the heck, eh? The

Wold Newton types start with the assumption that their core works are all

fictionalized and modified versions of adventures that really happened.

Names have been changed to protect the innocence, writers have omitted

certain facts, added certain ones in to liven up or fill in blank or dull

spots in the narrative. So, they're dedicated to excavating the 'true'

story from the fictional ones. Which means that they can do nifty things

like cross the works of different authors, something that I'm dabbling

with here. But it also means that they freely mix and match their mediums,

taking bits and pieces from everything from books to comic strips to movies

and television, without worrying as to the 'authenticity' or 'canonical'

nature of a story. Thus, as far as James Bond goes, an Ian Fleming novel,

a movie and a cartoon are all on the same level for instance. Of course,

when you're casting your net this wide, you pick up all sorts of contradiction,

but since these are fictionalized versions of real events, that means that

the contradictions are obviously invalid. And since there are gaps, one

is entitled to fill in the gaps between various fictional works by inventing

new facts, or even substituting the fictional facts for your new ones.

The result, occasionally is a towering incandescent mess which all too

often collapses under its own weight. The Wold Newton stuff works best

when it tries to stay tightly confined within a particular set of defined

canonical works.

For my own approach to these crossovers, I use a different

tactic. I assume that the events and information depicted in a work are

true, at least so far as the narrator or protagonist goes (a fine but important

point). And I try to be more stringent in defining my canons. One of my

favourite devices is the 'unreliable narrator.'

I'll give you an example: John Carter is a vicious, vicious,

vicious bastard. Now, the thing with Carter is that it's hard to realize.

All of his stories are narrated by him, and he sets great store by the

chivalric virtues. Yet while dueling a Thern in Gods of Mars, he

casually breaches Barsoomian chivalry by pulling out a pistol and shooting

him. Later in Warlord of Mars, dueling a superb Okarian, he distracts

the man and runs him through while his back is turned. Even later, while

spending time in the First Born Valley of Kamtol, he

sadistically and slowly cuts an inferior swordsman to pieces in a duel.

This is not a nice guy. It's true John Carter puts great store by chivalry

and has many fine qualities. But he's also got a mean streak a mile wide.

This is a man, after all, who went from being a slave to a chieftain of

Tharks in record time. The lesson: There are subtle discrepancies between

what John Carter tells us and what he actually does.

A similar case is Gulliver Jones, a man who is clearly

a petty thief. When you read Gulliver, one of the things you'll notice

is he's always casually and innocently tucking small valuable objects into

his pocket and then forgetting about them. Gulliver is also clearly not

one for long range thinking, despite several warnings of Ar-Hap's plans

to invade the Hither city of Seth, he never stops to realize or even thinks

to warn anyone. In short, the text of the novel presents to us, a picture

of Gulliver slightly at odds with, and substantially less flattering than

the Gulliver who narrates.

Then there's Julian of the Moon Maid, who works

quite hard to explain the Moon's inner world to us, but speculating with

only limited evidence and without a lot of background, it's quite likely

he gets quite a few things wrong.

And of course, the most practical example is Carson Napier,

a self-styled interplanetary explorer of boundless confidence, who, we

discover over and over, couldn't navigate his way out of a paper bag. When

you're with Carson, you're about to get lost, is the running theme of his

books.

All of this shows us is that the narrators are, to some

degree unreliable... Although that's an ugly word. The better term, perhaps,

is fallible. They can make mistakes, they can get things wrong, they may

misunderstand, misinterpret, jump to the wrong conclusions. Often their

observations are limited or partial, they, like the rest of us, must rely

upon what they are told.

So, in Journey to Mars, consider our protagonist, Frederick

Hamilton. Is he unreliable? Fallible? Consider this: On a planet with only

40% gravity, Hamilton concludes or accepts that his strength has apparently

doubled because the oxygen content in the atmosphere is slightly richer

in oxygen....

Hello? Duh! But let's be gentle with poor Hamilton, he's

not a scientist, he's a 19th century naval man transported to another planet.

Sure, he got it wrong, but he made an honest mistake. So the question is:

Is it possible he really is on Barsoom and that the discrepancies we see

are merely mistakes or misinformation on his part.

Here's another. The Martians believe, and thus Hamilton

believes, that Phobos and Deimos, Thuria and Cluros, are about to fall

from orbit. (Which might explain the participation of blue haired/skinned

Thurians on the Earth expedition). But, obviously, both in Hamilton's succeeding

novel, on Burroughs Barsoom, and in real life Mars, this doesn't happen.

Thuria and Cluros remain happily in place. Hamilton's Martians, and therefore

Hamilton himself, have simply gotten it wrong. Or Hamilton may have

misunderstood the time frame by twenty million years or so.

Does Hamilton's Mars really sport eight billion people,

or did he make a mistake transliterating Martian numerical terms into earth

ones? In fact, Burroughs himself made such a mistake when chronicling Martian

measurements, he left a critical unit out. Or possibly, did the Martians

themselves exaggerate their numbers, possibly to discourage him from thoughts

of Earth conquest, or to persuade him they were unstoppable or some other

reason.

They show him seas. Well, there are a few small seas left

on Mars. Omean, Korus, the Toonolian Marshes and Gulliver Jones Opal Sea.

We note that John Carter had returned to Barsoom in 1886 and had his adventures

in the Gods of Mars and Warlord of Mars between 1886 and 1892. So by this

time, Korus is no longer a lost sea, and hypothetically, might be a well

known tourist destination for a certain class of sightseers. Has Hamilton

simply misinterpreted what he saw, taking Korus or the Opal Sea for far

larger bodies of water?

Hamilton believes that Martian cities are built up along

the canals. Perhaps he really did see a few instances of this, and generalized

it to the whole planet. If he really does believe that there are eight

billion people, well they've got to go somewhere. So, a few limited observations

and some wrong information could build up some erroneous pictures of the

planet for him.

Diavojahr is described as half plutonian. Given the difficulties

Hamilton may have translating Martian into English, perhaps he's misunderstood

Instead of being from Pluto, perhaps his parentage is really partly from

an a 'plutonian underworld'.... Omean?

Unfortunately, without being able to read the novel itself

and analyze it in detail, it's hard to really make a firm argument that

Frederick Hamilton is on Barsoom. The best that I can say is that despite

apparent damning contradictions, it may be possible to resolve those contradictions,

and that the potential historical importance and the other close similarities

should entitle this story to a place on Barsoom. It may or may not fit,

but it seems a decent and even attractive possibility.

Unfortunately, for Gustavus Pope's posthumous reputation,

it appears that Richard Lupoff was a stronger champion than Sam Moskowitz,

and it was Gulliver Jones that claimed the glory and the reflected 'half

light' immortality. That said, I'd really love to find this some day and

go through it carefully, to see whether and how or if it might be fully

integrated into Barsoom, and whether we can identify the locations clearly

on Mars.

Continued

in ERBzine 1406

APOCRYPHAL

BARSOOMS: Part II

.

|

. . .. . .

. . .. . .

![]()

![]()